Earlier this week, I had an e-mail from a friend who is a long-time SF/F reader asking the

following question: “Why is it that some writers like to make up long names consisting of many, many consonants with maybe two or three vowels? They are completely unpronounceable. When I see them I frown. I recently started reading such a book, gave up and threw it away. What’s wrong with names that sound normal?”

While I’ve touched on names before (“What’s in a Name?” WW 3-24-13), this was partly autobiographical and partly related to writing. There’s certainly room to expand.

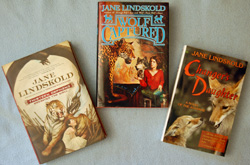

Obviously, I can’t answer for every writer. Although long names and terms are not something I use often, I have done it, especially when establishing a different culture. In Wolf Captured, Firekeeper, Blind Seer, and Derian end up in the country of Liglim. The language of Liglim is aggultinative – that is, shorter words combine to make longer ones (as is the case in many Germanic languages, including English, and in Japanese).

Since I wanted to make sure readers would know how to pronounce the words, I used a modified phonetic spelling. Therefore, for the character “Harjeedian,” I used “ee” rather than “I” in the second syllable, so there would be no confusion. However, for the final syllable, I did not feel the need to use a double “e” instead of an ‘I” because in the “ia” combination the “I” is usually pronounced rather like a long “e.”

Equally, for “Rahniseeta,” I used “ah” rather than just “a” for the first syllable, so there would be no question as to whether the sound indicated was a long or short “a.” Having, hopefully, established that in most cases a single “I” is pronounced as a short “I” I left that, but used a double “e” in the second to last syllable.

This seems to have worked, because readers who have spoken to me about the characters usually pronounce the names correctly. Oddly enough, it is the short word “Liglim,” that causes problems. I’ve heard it pronounced “Lee-gleem,” “Lee-glim,” Lig-gleem,” and, correctly, “Lig-lim.” So, obviously, shorter is not always clearer!

Ironically, the cover copy for Wolf Captured made up an entirely new word: Liglimoshti. This frustrated me quite a bit, since within the novel the culture is always referred to as the Liglimom. Ah, well… Just goes to prove the old saying, “Never judge a book by its cover copy.”

I want to go back to one part of the question that started all of this: “What’s wrong with names that sound normal?”

To this I answer, “What is normal?” I live in New Mexico, which is officially bilingual (Spanish and English). I am so used to seeing election ballots and other official documents printed in both English and Spanish that I’d find it “abnormal” to see a ballot that didn’t include both languages. Street names and place names go back with cheerful lack of rhyme or reason between languages. There’s one street that is Montaño (Spanish for “mountain”) for part of its length and then shifts to Montgomery. I suppose someone who didn’t know any Spanish could be forgiven for thinking Montaño meant “montgomery,” but I’m willing to bet that most people who live here know it doesn’t.

This takes me to the problem of writing a book that uses another extant culture. I’ve run into this quite a few times, most particularly in Legends Walking (aka Changer’s Daughter), part of which takes place in Nigeria, and in the “Breaking the Wall” series (first book, Thirteen Orphans) in which many of the characters are either Chinese or of Chinese descent.

English is commonly spoken in Nigeria, so I was fine there. However, from reading both novels set in Nigeria and non-fiction about the place, I rapidly learned that English was heavily salted with terms from many languages spoken by the various ethnic/linguistic groups that reside within the borders. I chose to follow the same custom, doing my best to carefully define terms within context.

However, this choice meant that I had to deal with the problem of how to deal with accent marks. See my “Accent on Page” (WW 1-11-12) if you’re interested in knowing how I dealt with this issue.

The “Breaking the Wall” books provided an entirely different challenge. Not only isn’t there one accepted way to transliterate Chinese, the “accepted” pronunciations often reflect the domination of Northern Chinese over the other dialects. People of my age probably remember when we were told that “Peking” was now “Beijing” – and that the name had not been changed, just how it was to be spelled and pronounced.

I did an informal experiment and learned something very interesting. Readers unfamiliar with the base language have more trouble “seeing” a foreign word, especially one that is oddly pronounced. In a novel about Chinese characters in which the names were given in Chinese, I had more trouble remembering the names than I did when the names were partly or completely translated. So “Master Li” or “Judge Dee” would stay in my mind, whereas “Qu Boyu” and “Zhongni” did not.

I checked and found this was the case for many people. Therefore, deciding that my job as a writer was to communicate, not to provide a language lesson, most of the time I gave the translations for the names, rather than making my readers learn another language and its conventions just to enjoy a series of novels. That it also saved me from having to decide which transliteration version to use. Not having to deal with whether to change the transliteration according to dialect, or whether the character was from “The Land of the Burning” (our world) or “The Land Born of Smoke and Sacrifice” (the alternate China) was a bonus.

Remember, familiarity with a language changes everything. Writers need to remember that they may have been working within their invented language, or within another culture for long enough that what was once odd has become familiar. However, this will not be the case for the reader.

Back when I taught college, one term I had three Japanese exchange students in one class. They were named Yumiko, Yukiko, and Yukari. I despaired of every getting their names right, but within a month I had no problem. However, it did occur to me that I would not have had the same problem if my students had been named “Ann,” “Andrea,” and “Angela.” It was the combination of the unfamiliar first letter “Y” (not very common in English – and even names like “Yvonne” and “Yvette” are often mispronounced) and my lack of familiarity with the language’s conventions.

In the years since, I have learned a lot more Japanese and probably wouldn’t have the same problem. “Yukiko,” for example, would automatically break down into “yuki” (snow) and “ko” (a common feminine suffix, roughly translated as “child”).

So, to answer my friend’s question, what seems unpronounceable may not be unpronounceable, what is normal may not be normal, but when writing you should never forget that you’re communicating and owe your readers a bit of a bridge.

February 27, 2013 at 8:46 am |

Neat points!

I’ll add something very similar I noticed recently: the difference between pronouncing vowels in Hawaiian and Korean.

When written in English letters, they both look like they have a lot of vowels, yet they are pronounced differently. In Hawaiian, it’s safer to pronounce every vowel. Haleakala can be pronounced Hale a ka La, or “House of the Sun.” While Korean also has vowel trains (namjaai=boy child, pronounced namja ah ee), in most cases multiple vowels in English are translations of single Korean vowels (ae, eo, yae, and many others are single sounds.).

This gets interesting when someone used to Korean tries to pronounce a vowel rich Hawaiian word. Oahu can come out as “Wahoo,” or Haleakala can be “Ha leak ala.”

For those making vowel-rich fictional languages, this can get interesting. Unless there are clues in the text, pronunciation can get warped in interesting ways.

February 27, 2013 at 2:01 pm |

I like your point about a writer’s job being to communicate. The corollary is that things that impede communication should be avoided. Of course, there’s lots of room to break this rule for artistic or philosophical reasons (which could be considered communicating something on a different level. Could art be classified into a hierarchy of how or what is being communicated? Huh. I’ll have to think about that.)

Sometimes foreign languages or conlangs can definitely get in the way of a story, though. Names don’t bother me too much, usually. If the name looks funny and unpronounceable, I kind of skip reading it, and just use the word as visual gestalt to represent that character, rather than breaking down into sounds. That can make it harder to remember what the name actually is.

But the problem comes from English orthography. We have twenty-odd consonants to represent more than forty sounds. In general, I’d like authors writing in English to use unambiguous spellings of made-up words and names, while recognizing that sometimes it just doesn’t work that way.

However, I recently started a computerized French language course, and I am finding French orthography very difficult. It’s almost like I have to forget everything I think I know about how the Roman alphabet works, especially in regard to syllable formation. I’m not sure how consistent French pronunciation of individual letters is compared to English, but in my cynical moments it seems that the general rule is to pronounce the initial consonant, push a vowel through your nose, and then swallow the last half of the word.

March 1, 2013 at 7:13 am |

Snort! [messy, if you push that through your nose ;)]

AAMOF, thanks to Les Immortels standard French pronunciation is pretty consistent. Enough so that they always look embarrassed when I point out the vagaries of ‘ix’ or one of the other rare cases.

Two things to keep in mind are that, like the Korean mentioned upthread, vowel groups are usually a single sound – and accents flag most of the cases when they aren’t – and words beginning with a vowel are almost invariably elided to the consonant at the end of the previous word.

March 1, 2013 at 9:13 am |

I share Chad’s problem with pronouncing French, complicated by Spanish having become my default. Once embarrassed myself horribly…